Contributed by Nilani Mathur

A Short History

The term ‘it girl’ sounds like a deceptively modern compliment. Yet, they’ve been throned across decades, beginning in the 1920s with American actress Clara Bow, who is now referred to as the original. She was born into a couple of violent, mentally deranged parents and a tenement slum in Brooklyn. Her first moment of fame came in 1921 when she was merely sixteen—she had submitted to and won the “Fame and Fortune"acting contest sponsored by Motion Picture Magazine. This quickly sent her off into long days and nights of work in New York and Hollywood films, 46 silent films and 11 talkies, before she died in 1965.

What defined her ‘it’ factor was “being comfortable in her own skin” while representing the modern, short-haired and short-hemmed flapper woman, per Nicholas Barber at BBC. According to her biographer David Stenn, Bow carried “a naturalism that hadn’t been seen before.” That naturalism is potentially the defining quality of all ‘it girls’—a common denominator of effortless beauty and femininity.

But what does this cultural obsession with effortless femininity reveal about us? Why do we repeatedly crown women for appearing untouched by the rigor, ambition, and labor that femininity often requires? To dissect the It Girl is to dissect a paradox: she is both a product of her time and an idealized escape from it, a woman who embodies a decade’s desires while appearing somehow immune to its pressures. Through each era, the archetype evolves through subtle shifts in what the culture wants to see in her, and, equally, what it wants to hide.

Breaking It Down by Decade

1920s

The 1920s marked the first visible rejection of Victorian restraint, and with it, the It Girl became synonymous with freedom. The It Girls of the decade, like Clara Bow or Josephine Baker, exuded modernity with short hair, short hemlines, and an irreverence that scandalized polite society. Bow’s flapper roles portrayed her as cheeky and free-spirited, while Baker, in Paris, transcended this with her audacity and fluidity on stage. Her refusal to conform made her untouchable and magnetic—she was the first Black woman to star in a major motion picture, the 1927 French silent film Siren of the Tropics, directed by Mario Nalpas and Henri Étiévant. The It Girl of the ’20s was proof that femininity could be playful, sexual, and unapologetically modern.

1930s

The 1930s replaced the chaos of the flapper with an It Girl defined by restraint, polish, and cinematic charisma. Norma Shearer, who was once dismissed as too plain to succeed in Hollywood, became MGM’s queen of “sophisticated” roles, portraying liberated yet refined women. Her appeal wasn’t overtly rebellious, but she seemed to bear a knowing confidence or an unassailable poise, even when playing unruly characters.

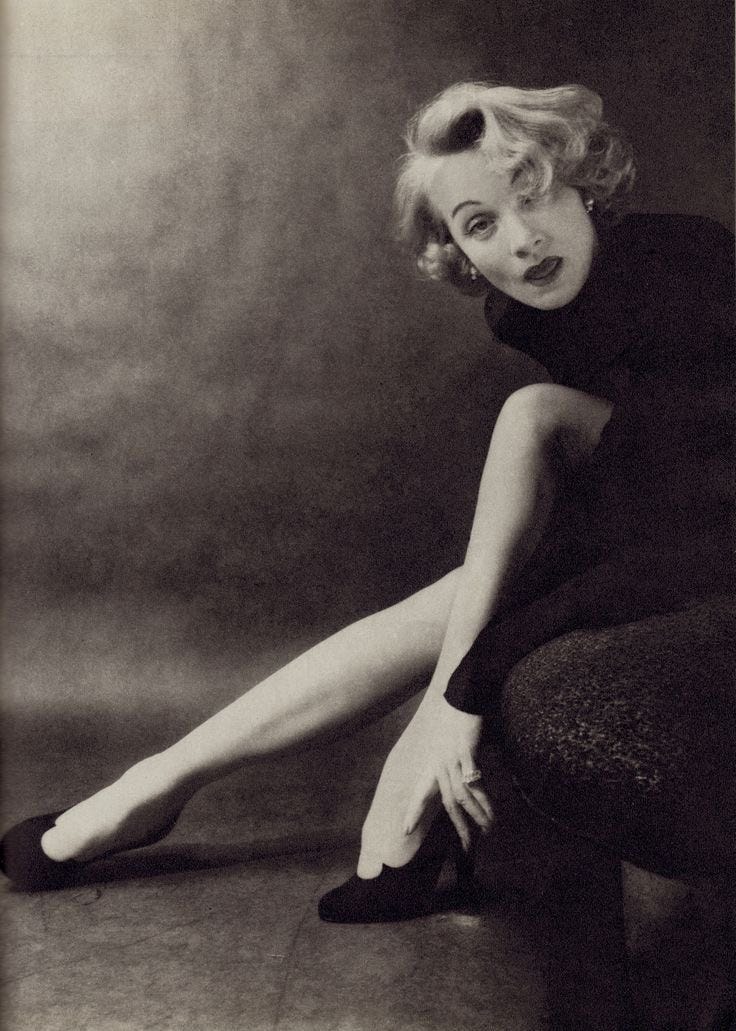

Marlene Dietrich, marked by her angular cheekbones and androgynous style, offered a sensual intelligence that was, perhaps, decades ahead of its time. She was a German-born cabaret singer before becoming an international film star, and she tested the softness of traditional femininity with the sharp precision of her image.

1940s

The 1940s built upon this cultivated spirit, but with a more deliberate form of glamour. Lauren Bacall, plucked from modeling at just 19, made her screen debut opposite Humphrey Bogart with a sultry, half-lidded gaze, earning her the nickname “The Look.” Her low voice and slow, intentional movements furthered her appeal.

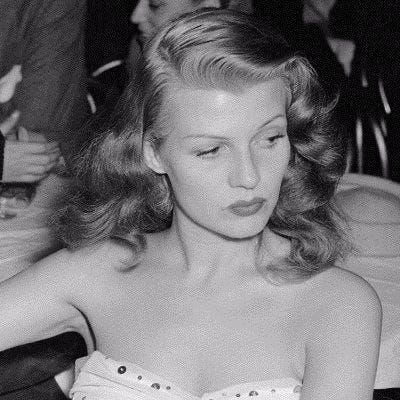

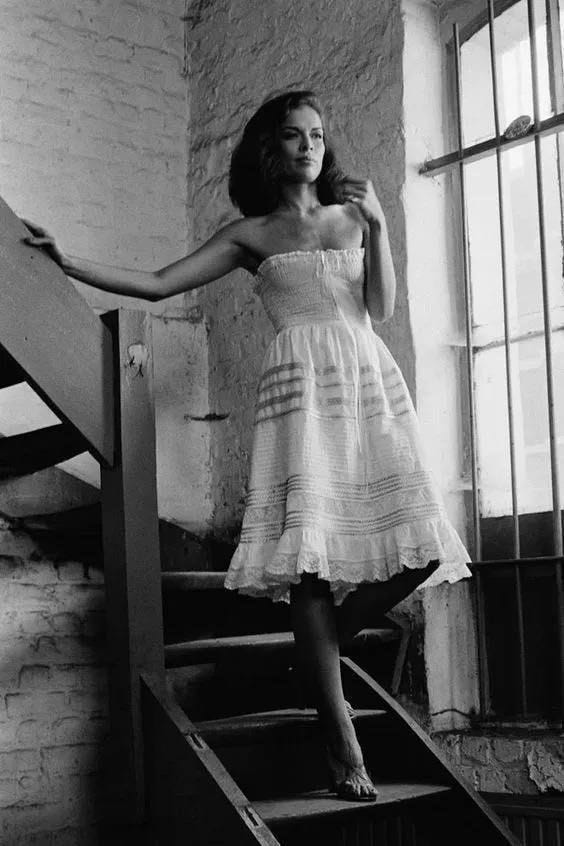

Rita Hayworth, known as “the Love Goddess,” embodied the studio era’s ability to manufacture an ideal. Her vivid, red hair and polished sensuality were the result of Hollywood reinvention, but her allure remained seemingly effortless. Together, Bacall and Hayworth marked an archetypal shift from the playful woman to the kind who commanded desire by merely existing.

1950s

The It Girls of the 1950s simultaneously represented a controlled and an undone perfection. Grace Kelly, the taut, regal, ideal American actress-turned-princess, had a style that was crisp, understated, and refined. Her enticement lay in her composure—she seemed as if nothing could disturb her pleasantness.

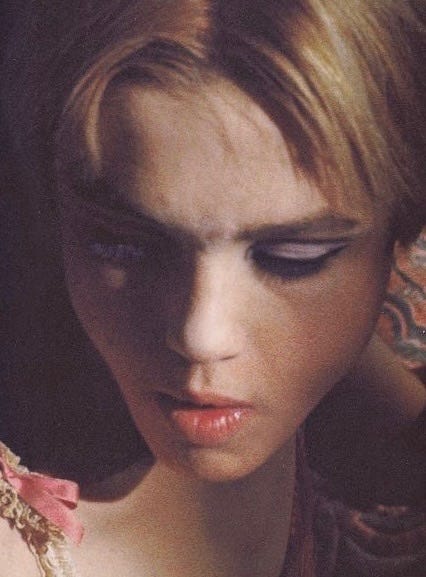

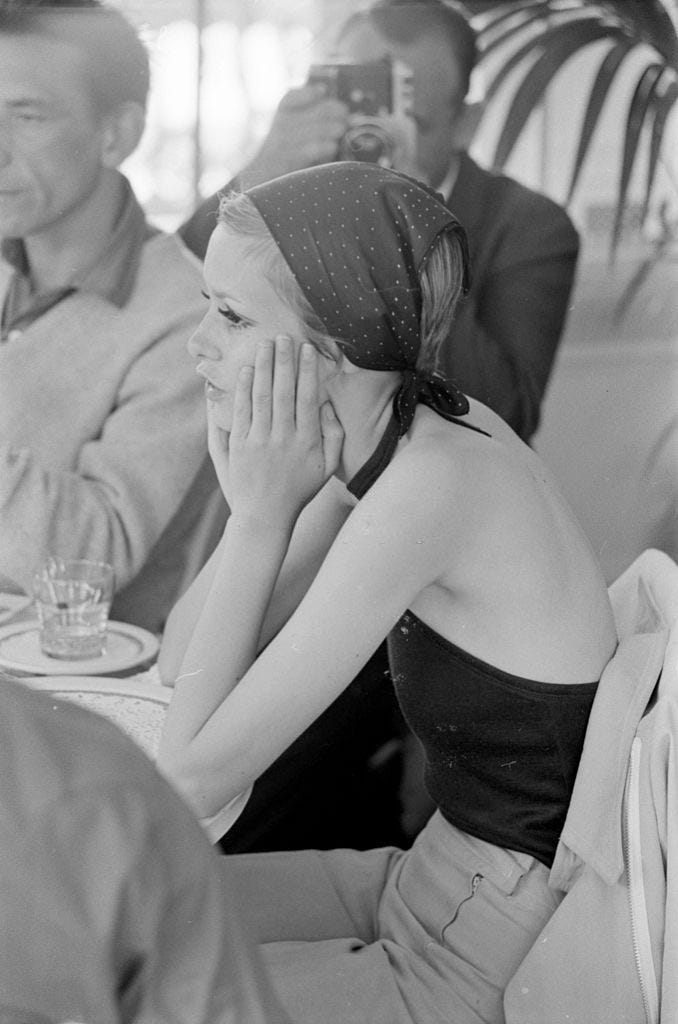

Brigitte Bardot, however, was in many ways the counterpoint to Kelly. Bardot, a French actress and model, brought a sensuality that felt unstudied and free. Her tousled hair, winged eyeliner, and intrinsic confidence characterized a contemporary beauty—disorganized, disheveled, and all the more striking because of it. Kelly and Bardot defined the decade’s duality—that femininity could be either controlled or carefree, but both required an illusion of ease.

1960s

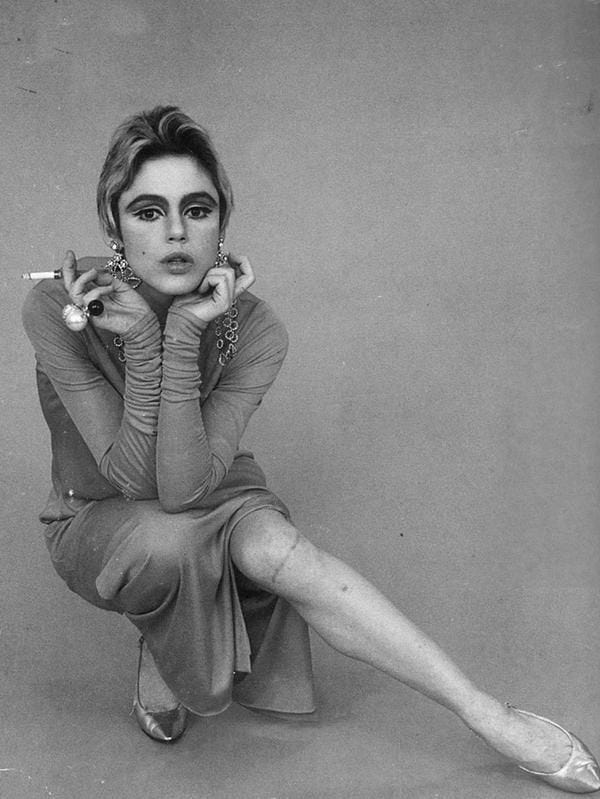

The 1960s It Girls were less about perfection and more about persona. Edie Sedgwick, the wealthy Massachusetts debutante turned Warhol muse, was a figure of both glamour and chaos. Her platinum pixie cut, chandelier earrings, and black tights made her a fashion inspiration, but her fame was inseparable from her personal turbulence.

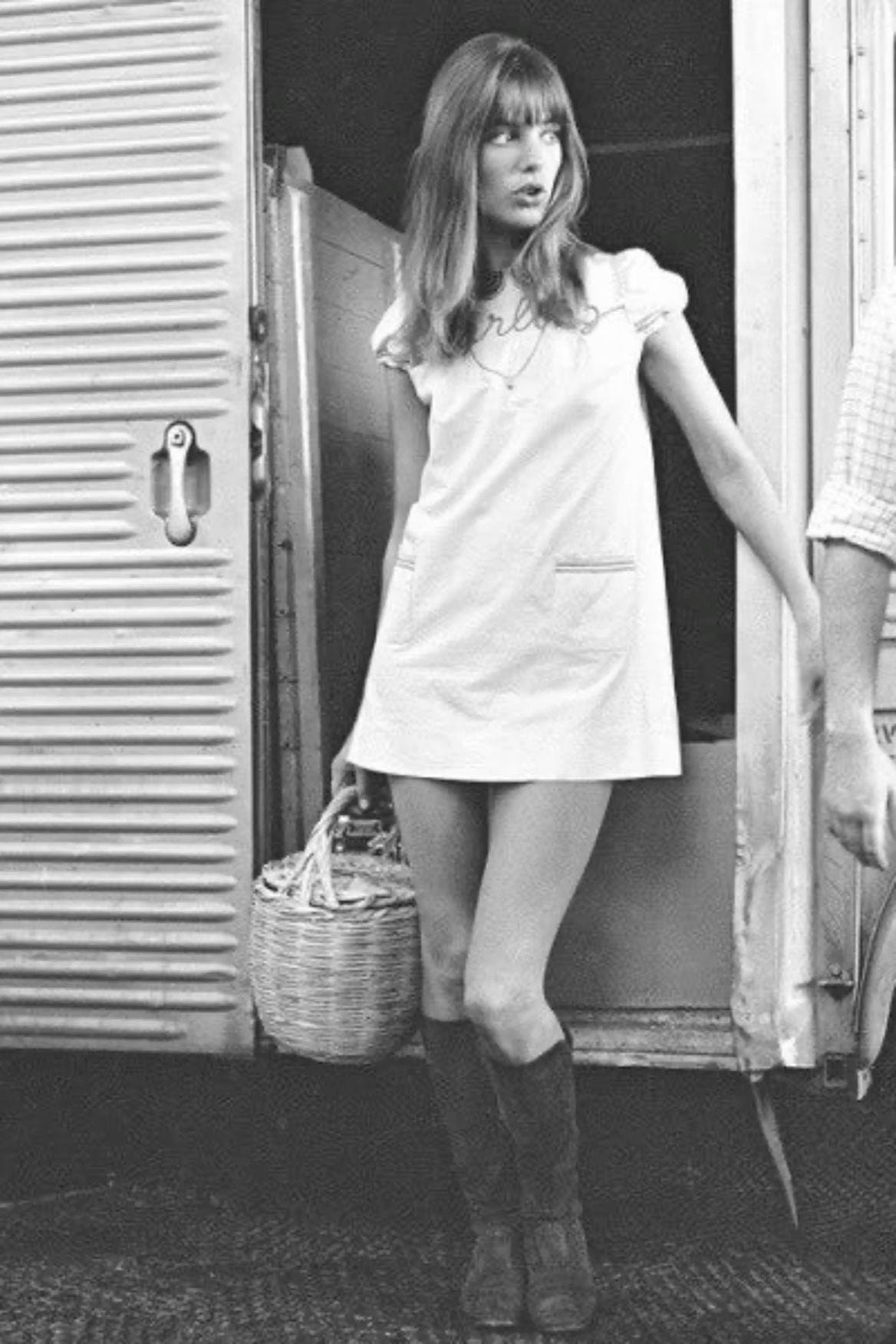

Jane Birkin, the English singer and actress who became a French style icon, offered a different energy. Her appeal was soft and casual, characterized by her white tees, basket bags, and bare face. She represented the sort of woman who lived—who walked everywhere, whose hair was often unstyled, whose bag, despite being Hermes, was bruised and overflowing with chaos and possessions.

Twiggy, discovered at just sixteen in London, defined the mod look with her sharp pixie cut and painted lashes, presenting a discrepant standard of youth and androgyny. These women shifted the It Girl away from the sculpted enchantment of earlier decades toward something spontaneous, or at least one that felt that way.

1970s

The 1970s It Girl lived at the crossroads of fashion, music, and nightlife. Bianca Jagger, born in Nicaragua and married to Mick Jagger during the height of the Rolling Stones’ fame, became a symbol of Studio 54 decadence. Her white suits, plunging gowns, and effortless poise turned her into a fixture of the disco era’s glamorous chaos.

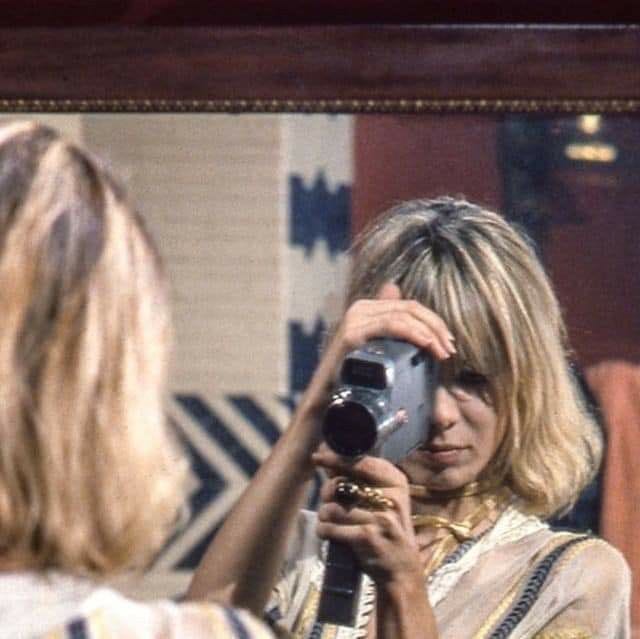

A notable and discrepant example of the 70s archetype is Anita Pallenberg. She was a camp follower distinct from the many other groupies of the era, but was never quite separate from the scene. The German-Italian actress and model entered the Rolling Stones’ inner circle through Brian Jones, and later became Keith Richards’ longtime partner, maintaining a volatile connection with Mick Jagger. Pallenberg defined much of their aesthetic. Her fur coats, messy blonde hair, and sharp, bohemian style became synonymous with rock-and-roll cool, making her one of the first women to turn the role of “muse” into something more commanding, even if still tied to the male gaze.

1980s

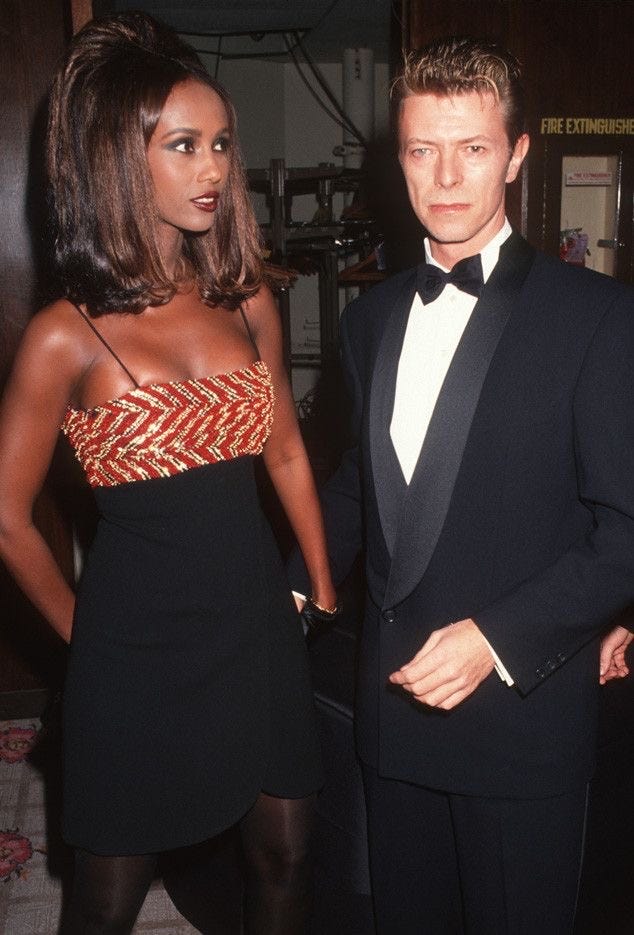

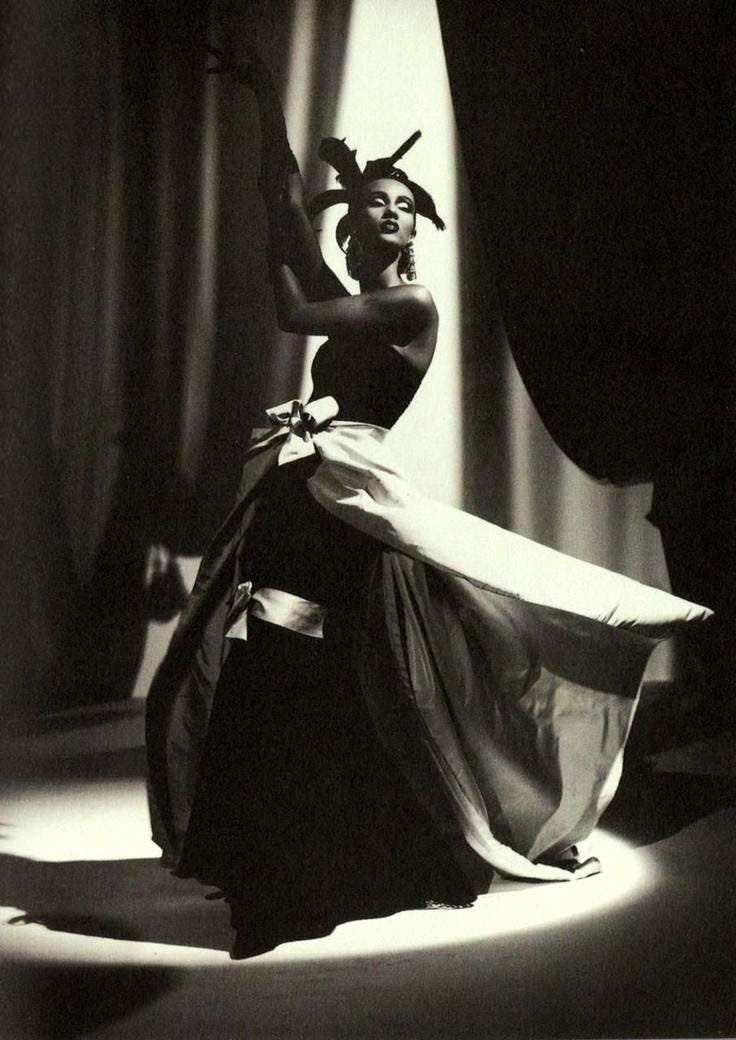

The 1980s transformed the It Girl into a commodity, someone whose allure was defined and amplified by the rise of mass media, advertising, and global fashion houses. Iman, born in Somalia and discovered by photographer Peter Beard, redefined the modeling world by resisting most Western beauty standards. Her embodiment of elegance and strength made her a muse to designers like Yves Saint Laurent, who famously said he could never create without thinking of her.

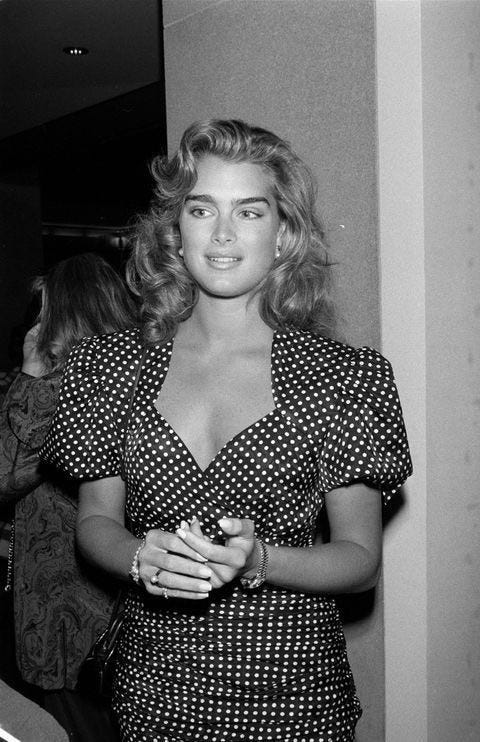

Brooke Shields, on the other hand, revealed how beauty can be both marketable and controversial. By the age of 15, she had stirred public debate with roles that blurred the line between innocence and sexuality, and her Calvin Klein and Playboy ads cemented her as both a cultural phenomenon and a symbol of how femininity was being packaged in the consumerist 80s. The It Girls of this decade were marked by the ability to turn image into empire and to be as ethereal and iconic as the brands they represented.

1990s

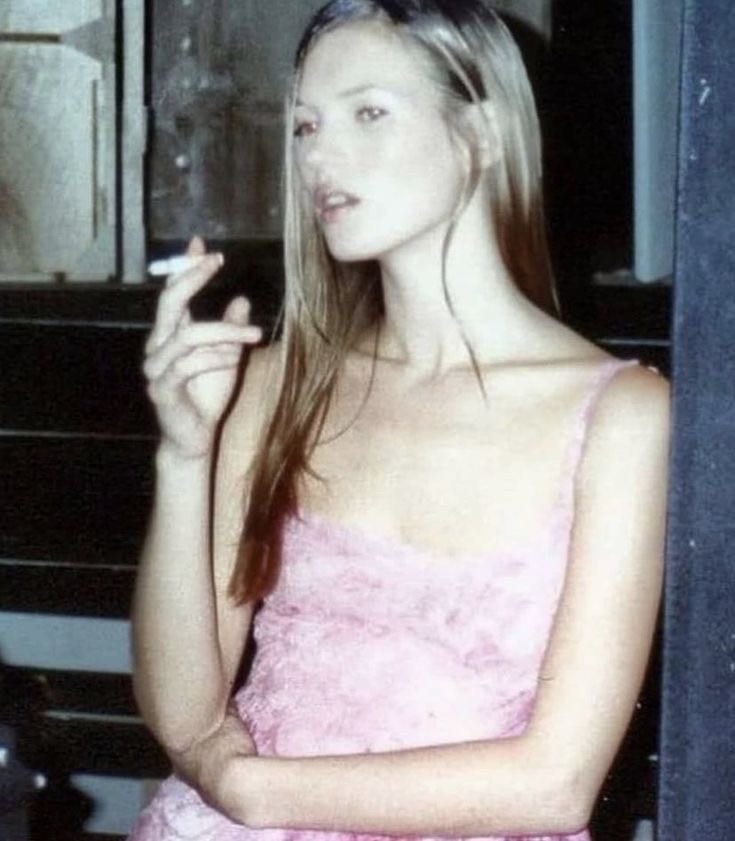

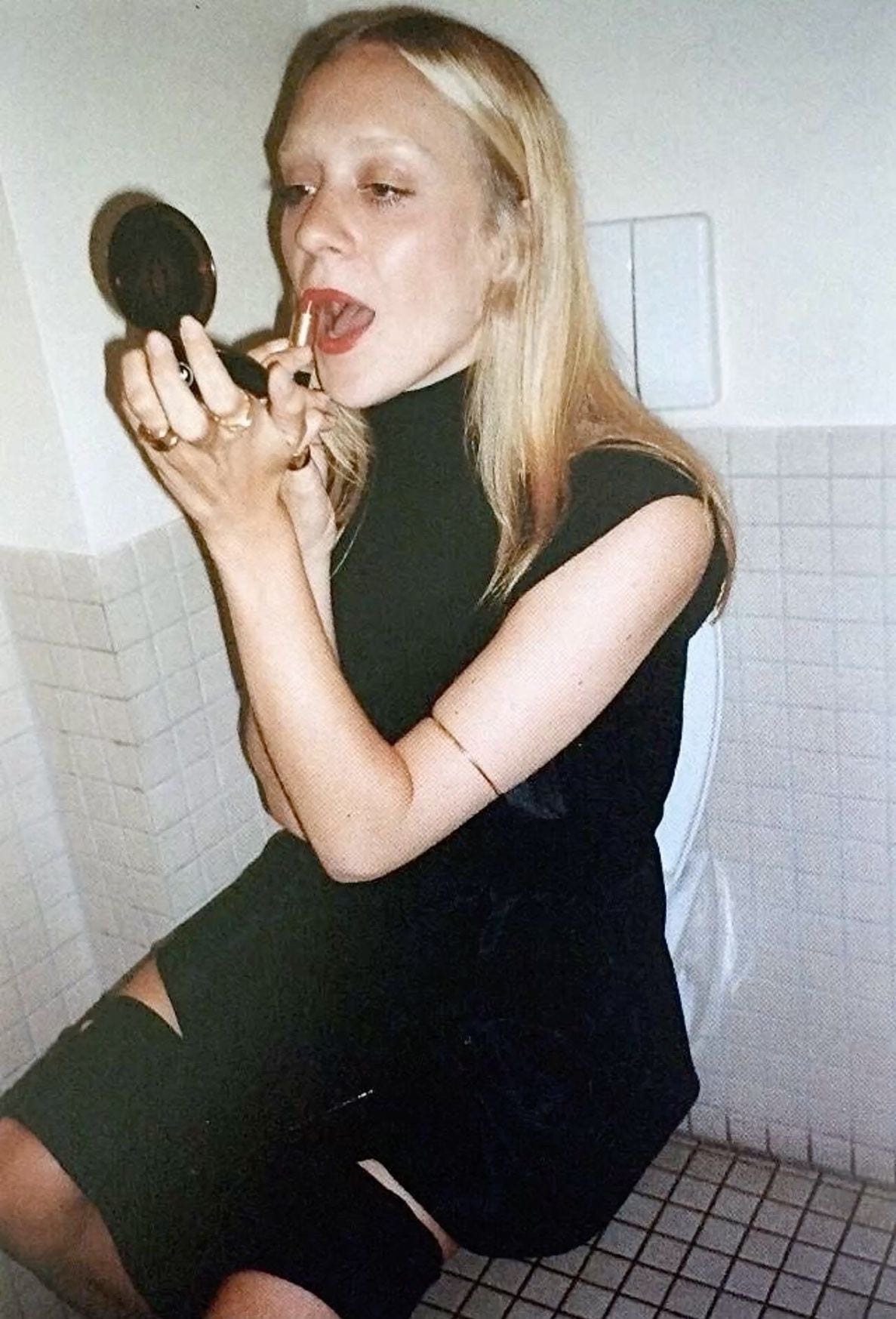

The 1990s ushered in a rejection of the excess of the 80s, replacing it with a raw, understated cool that defined the decade’s It Girls. Kate Moss emerged from the London modeling scene as the antithesis of the polished supermodels before her. With her waifish frame and tousled hair, Moss reinstated beauty as flawed, playful, and honest. Her rise coincided with the grunge and heroin-chic aesthetics, rendering her both a fashion icon and a reference for debates about glamorizing self-destruction.

Chloë Sevigny, an actress and style maverick, carved out a niche by blending indie sensibility with high fashion. She symbolized a shift toward celebrating individuality over conventional glamour and is known for her eclectic wardrobe and nonconformist attitude. Sevigny’s charm lay in her unpredictable mix of innocence and edginess, embodying a cool that was authentic and accessible.

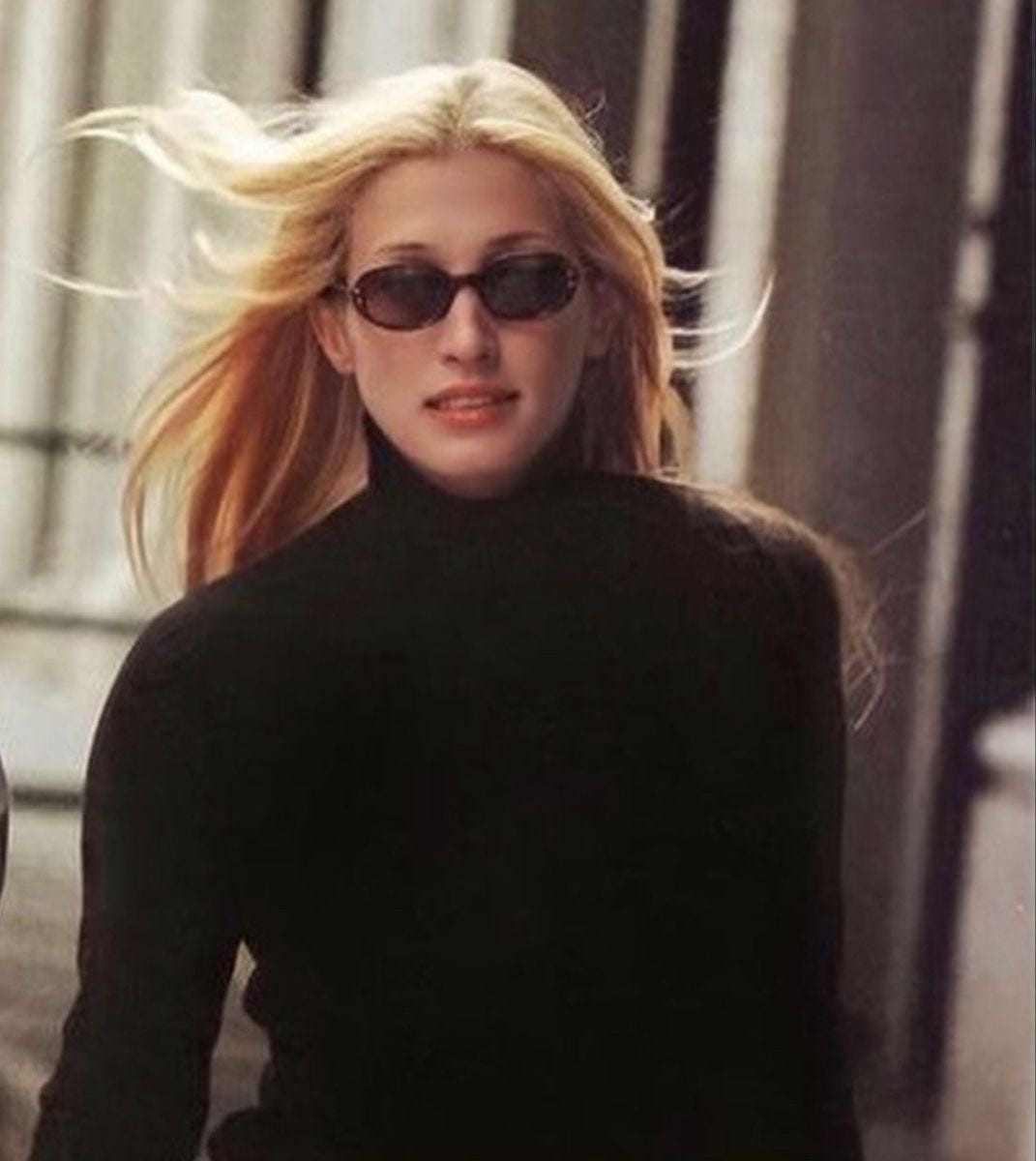

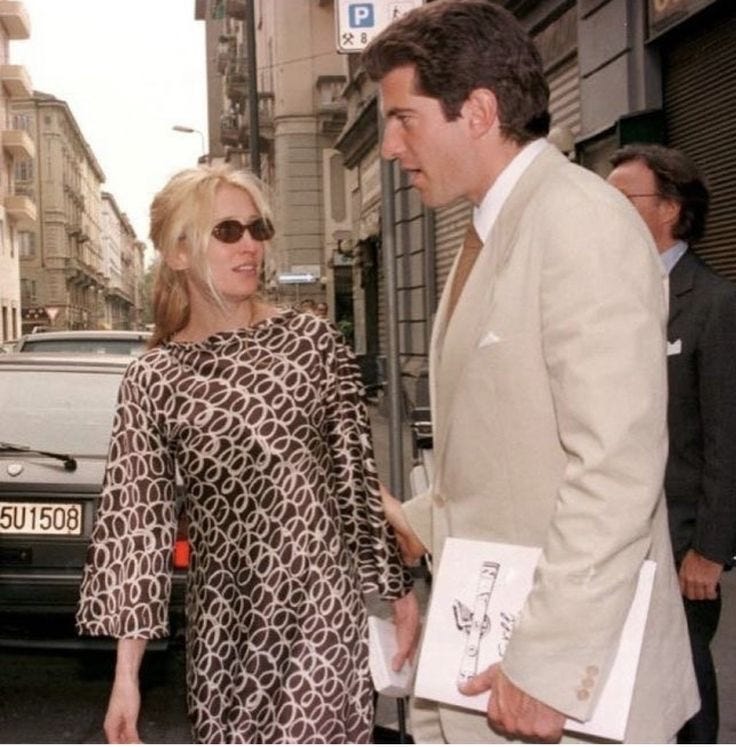

Carolyn Bessette-Kennedy, meanwhile, projected a different archetype of the decade—minimalist, polished, and timeless. As a style icon of the American elite and wife to John F. Kennedy Jr., her simple white tees, perfectly cut blazers, and pared-back makeup captured a modern, refined elegance. Her beauty signaled a mastery of restraint and, as a result, a new dimension of feminine cool. These women illustrate how the 90s It Girl moved beyond mere appearance to embody a more complex relationship with identity—effortless beauty was inseparable from attitude, individuality, and cultural rebellion, even if subtle.

2000s

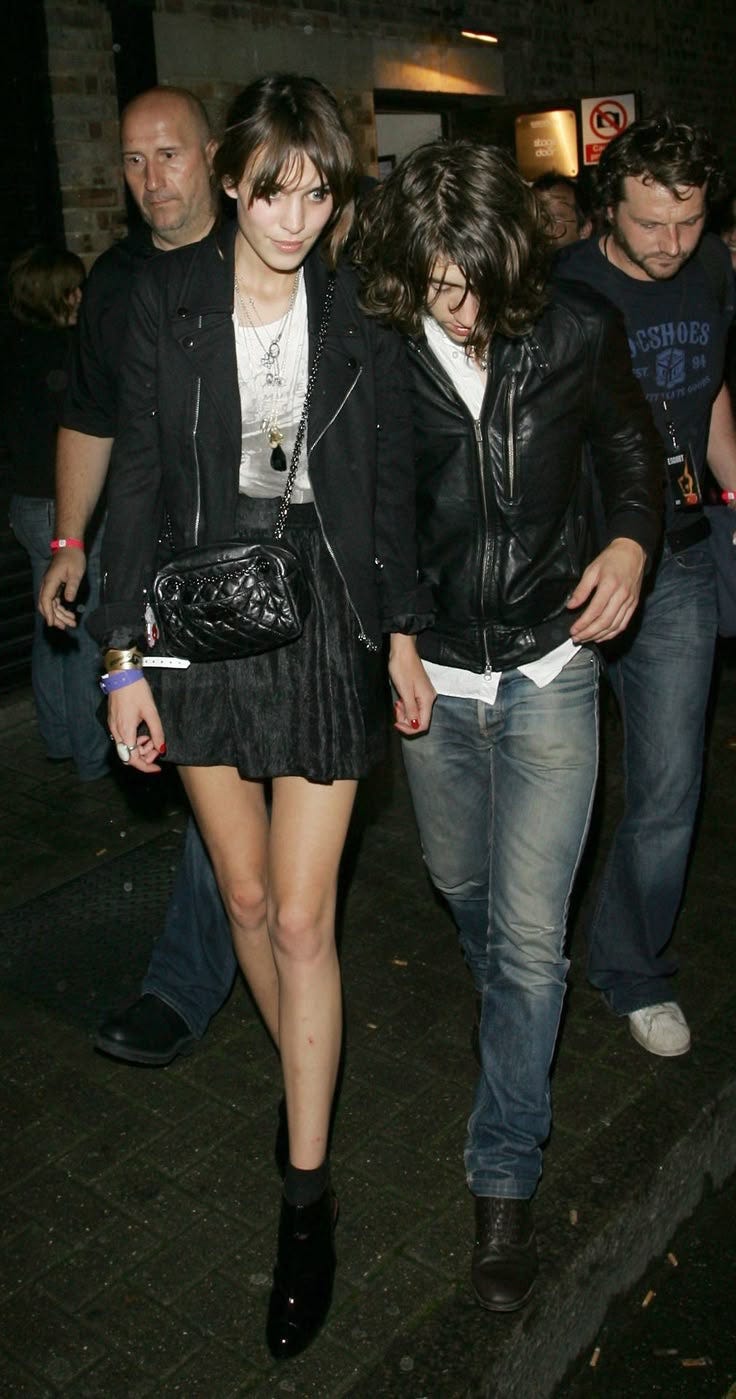

The 2000s marked a turning point, where the It Girl became less about Hollywood studio polish and more about cultivating an off-duty, street-style aesthetic. Alexa Chung defined this shift with her mix of British nonchalance and fashion-forward instinct. A television presenter turned fashion muse, Chung’s messy bob, oversized sweaters, and boyish flats made her the poster girl of “effortless chic.” In 2007, Chung began dating Alex Turner, the lead singer of The Arctic Monkeys, which also put her under the “rockstar girlfriend” narrative.

Mischa Barton, propelled to fame through The O.C., became the face of early-2000s Los Angeles glamour. Her style combined bohemian layers, oversized sunglasses, and a laid-back attitude that resonated with a generation raised on celebrity paparazzi culture. But what set Barton apart was her aura of untouchable cool during the height of the tabloid era—she looked like she’d stumbled into stardom rather than chased it.

Lucy Liu brought a different energy to the decade’s It Girl canon—sleek, sophisticated, and commanding. From Ally McBeal to Kill Bill, Liu’s roles and personal style balanced intelligence with understated glamour. While Chung and Barton embodied a form of casual dishevelment, Liu projected a more intentional, confident femininity that still felt effortlessly modern. The 2000s It Girl, then, was not just a style icon but a cultural hybrid of media influence and personal branding.

2010s

The 2010s redefined the It Girl as both a cultural figure and a personal brand, with social media blurring the line between authenticity and performance. Zoë Kravitz embodied this tension perfectly. As the daughter of musician Lenny Kravitz and actress Lisa Bonet, she inherited a natural cool but made it her own with her mix of undone braids, loose tailoring, and genre-bending roles in film and music. Much of her fascination lay in how she managed to appear both intimate and invulnerable, sharing just enough of herself to feel real while maintaining an aura of mystery.

Sky Ferreira, a singer and model, offered a rawer version of this cool. Her bleached hair, thrift-store aesthetic, and deliberately unpolished attitude made her feel like an antidote to the hyper-gloss of mainstream pop culture. She didn’t try to be likable or perfect; her “effortlessness” was born out of a visible refusal to play by the rules, which only heightened her allure.

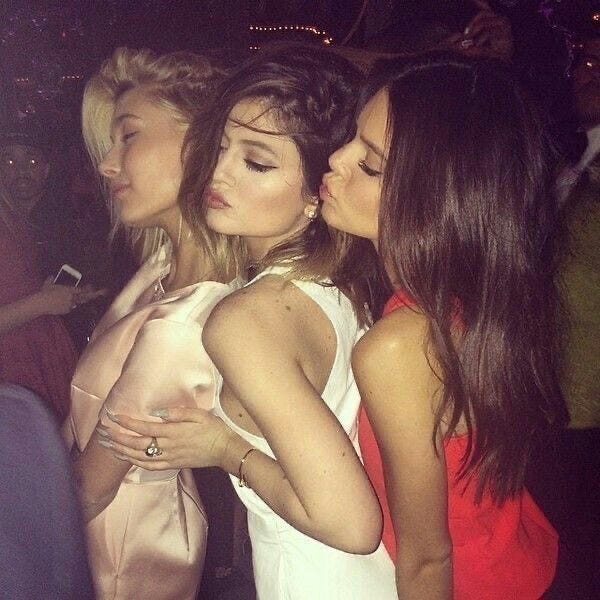

Kylie Jenner, in contrast, represented the opposite extreme of the 2010s It Girl: hyper-curated, constructed, and fully digital. From reality TV to the creation of her cosmetics empire, Jenner’s image was built on a mastery of social media performance. Yet even her meticulously staged persona was marketed as natural and relatable—an illusion of effortlessness designed for the Instagram age. In this decade, the It Girl was someone who shaped her “effortless” allure into a more deliberate narrative.

2020s

Today, the It Girl is defined by extremes: on one end, there’s a return to a softer, quieter kind of beauty, and on the other, a fascination with darker, more chaotic aesthetics. Taylor Russell embodies the former. Known for her breakout roles in films like Bones and All and her collaborations with fashion houses like Loewe, Russell’s charm lies in her warmth, intelligence, and quiet elegance. She comes across as soft-spoken and thoughtful, with a natural grace that feels rare in a hyper-online era.

Emma Chamberlain, by contrast, built her It Girl status on relatability and digital intimacy. Transitioning from candid YouTube vlogs to fashion-week interviews, she’s managed to stay approachable while becoming a fixture of high fashion—a testament to how this era prizes adaptability as much as authenticity.

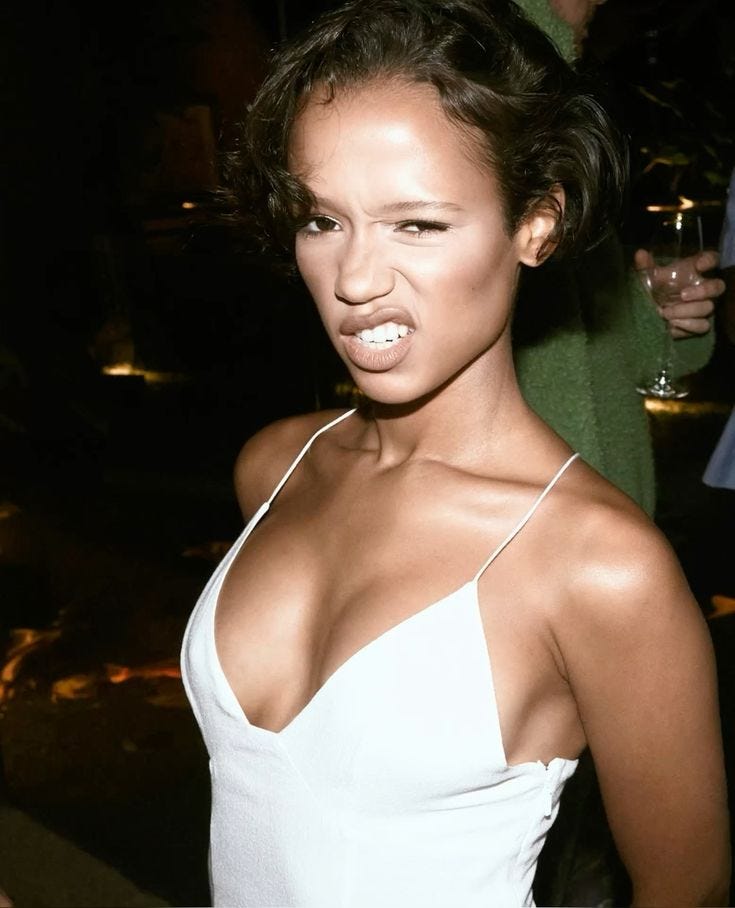

Gabriette, model and influencer, represents the opposite pole: sharp, subversive, and deliberately provocative. Her look—black lipstick, scanty eyebrows, and grunge-inspired styling—feels like a rejection of curated perfection. Gabriette being close friends with Charli xcx and them both currently having relationships with members of The 1975 seems to enhance her edgy, almost nostalgic energy.

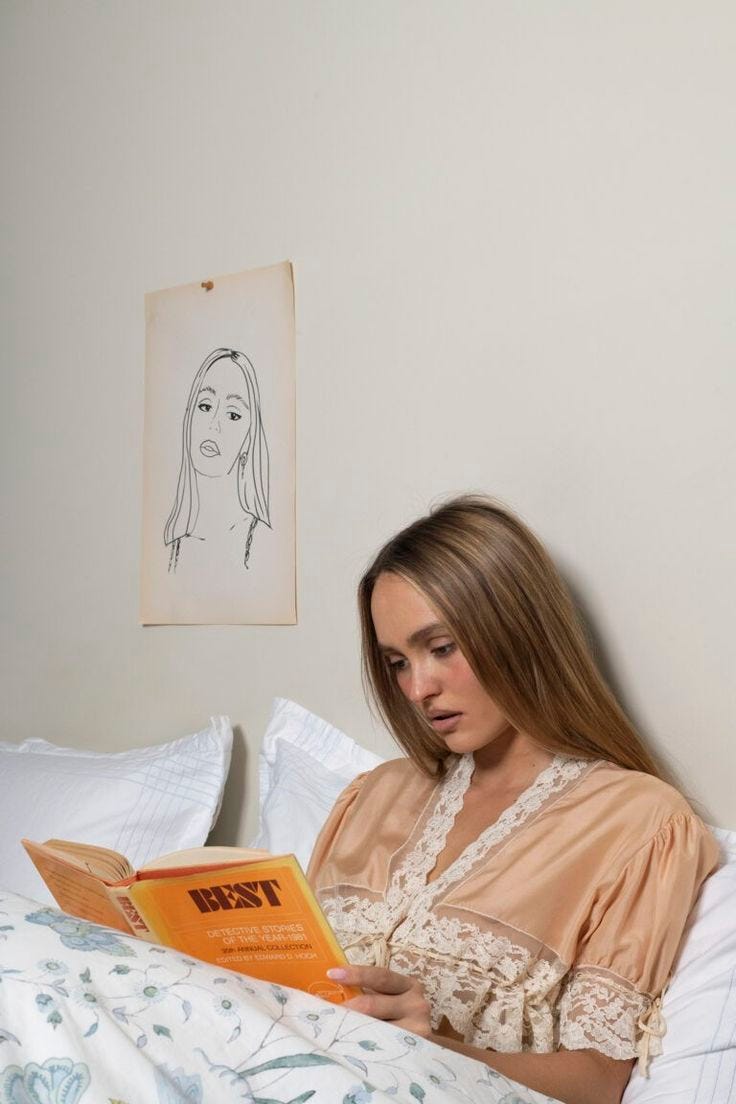

Lily-Rose Depp, with her French-girl minimalism and famous lineage, sits somewhere in between. She merges old-Hollywood glam with a modern sense of detachment, seeming effortlessly cool while never revealing too much of herself. The 2020s It Girl reflects a fragmented culture: some are admired for their softness and depth, while others embody a kind of wildness, yet both are bound by the misconception that their allure is completely uncrafted.

The It Girl archetype reveals more about us than it does about the women themselves. Across every decade, our cultural fascination with “effortlessness” reflects a collective longing for what feels natural in an increasingly constructed world. We reward women who make beauty, charm, and success appear innate and never labored for or strategic. But in reality, It Girls are crowned not because they are untouched by effort, but because they have mastered the art of concealing it. What shifts across eras is the form that concealment takes—be it the flapper’s carefree rebellion, the 50s’ immaculate poise, the 90s’ anti-gloss chic, or the 2020s’ mix of soft warmth and eclectic cool.

We project our desires and insecurities onto these women, turning them into symbols of what feels just out of reach—a kind of perfect unselfconsciousness, which never entirely exists. Ultimately, our obsession with the It Girl uncovers something significant about the cultural narratives we cling to: we want femininity to appear natural and untamed, even as we demand that it be carefully sculpted and endlessly adaptable to shifting ideals. In every era, the It Girl stands at the tension between who she is and whoever we need her to be.